Intro: The Quinn Connection

"The Quinn Girls" - those words harken back to a time when all eight members of my family lived in a three bedroom house along Pogue's Run in

Oglebay Park.

Why did we live in a house in

Oglebay Park?

In 1950, my father,

George H. Breiding was hired as the Naturalist for Oglebay Park and worked at the

A. B. Brooks Nature Center there.

The illustration below was drawn by Naturalist and artist Don "Bud" Altemus, a contemporary of my dad's. The drawing was produced for the Nature Center stationary.

He served as Naturalist there until 1963 - 13 years.

He served as Naturalist there until 1963 - 13 years.

During those 13 years 3 more children were born to George and Jane Breiding - Michael, Wayne and William. My mom had already born three other children and had one mis-carriage before I came along in 1952.

During my dad's 13 years at "the Center" he was seldom home. Six days a week, sometimes seven he would get into the Ford Fairlane station wagon and drive the circuitous route up Pogue's Run Road and the old Serpentine carriage road to Rt 88 and then over to the Nature Center.

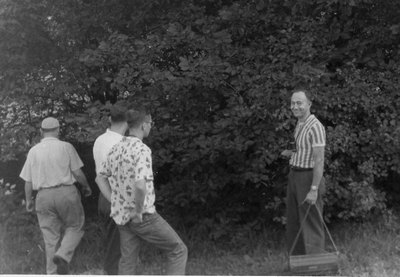

My dad took his job seriously. Among many other activities, during those 13 years he led 1000s of nature walks.

George H. Breiding's first nature walk at Oglebay Park in June of 1950

Photo by Bill Wylie

He also arranged and led winter bird walks where as many as 100 adults and children would show up. These bird walks usually ended with steaming mugs of hot chocolate and a crackling outdoor fire in the open-air fireplace on the lower level of the Nature Center.

Then there was Junior Nature Camp, Mountain Camp, a weekly radio show and newspaper column, evening slides shows and movies, participating and leading events with the

Brooks Bird Club, shooting, preparing and making study skins of song birds, public relations and the list goes on. Is it any wonder I saw my dad more at the Center than at home?!

My memories of those childhood years at Oglebay Park could fill volumes. And, in one of those volumes there would be a chapter on "The Quinns".

Like the Breiding's - the Quinn Family was big. There were 9 children of Tom and Virginia Quinn, 6 girls and 3 boys. They attended many of the functions at the Nature Center and I often heard references to the "Quinn Girls", usually by would be suitors and admirers, some of whom worked for my dad.

I confess to only dim memories of the Quinn family from back then. I don't remember the boys at all and the "Quinn Girls" are now only shadowy shapes with lovely smiles, giggles and flowing skirts.

How I wish I had been just a few years older... :^)

Fast forward to 2012. I am now on my way to visit Patti (Quinn) Greeneltch and her husband Ned in Cottonwood AZ. Patti had graciously extended (several) invitations to me to stop by and visit on my various trips west. It took me a while, but I finally got around to it. And, am I glad I did. Although I felt I barely knew Patti, when we met again that feeling vaporized in a matter of seconds. Amazing how that works.

In order to jog my memory and fill in some blanks I asked Patti to provide me with a brief history of the Quinn Family.

I (Patti) am the youngest of nine. In order;

Melissa (lives in Portland, OR), Tom (lives in Moundsville), Amy, lives in Dallas, WV, Louise, lives in Pittsburgh, Kathleen, lives in Wheeling, Suzie, lives in Dallas, WV, Mike, lives in Hazen, ND, Colin, deceased and me.My mother's father (Russell B. Goodwin) was the mayor of Wheeling in the 50's, my dad (Thomas W. Quinn) was from Moundsville, worked everywhere as a salesman but probably for the longest as an oil and gas man (leasing land from farmers for drilling companies).

We were told that my parents met at a birding/pancake breakfast at the Nature Center led by A.B. Brooks. My dad always had a love of the out of doors and often took as many children as could fit off camping, sharing his knowledge of geology, plants, etc (he was in the Boys Scouts as a young man).

He was involved in Terra Alta in the early days with Dan Hile, George Breiding and the founders of camp. As children we would often camp at Terra Alta during the "off-season". We all have many fond memories of the camp. Several of my older sisters attended Nature Camp as campers and as counselors.

My sister, Suzie (Quinn) and Joanie (Breiding), were good friends at camp and Joanie was my first and favorite counselor. My brother Mike helped at Nature Camp during his college years.I moved back to Wheeling in 1975 and when my children were young they went to Nature "day camp" and then went on to regular (Junior Nature Camp) camp. My older son, Corey, loved it and stayed involved for many years, worked at the Nature Center as a day camp counselor during his college summers.

I volunteered at the Nature Center for many years, doing Oglebayfest, Winter Camp, Halloween Night walks, pretty much whatever I could do to help. I had the opportunity to renew my friendship with Dot and Delores (Broemson/Duvall), Carl Slater and others from my younger days, and to be a member of the OI Nature Center Board . I worked with Greg Park at REAP for a few years and then helped with both (Junior) Nature Camp and (Mountain Camp at) Terra Alta. I enjoyed leading the campfires at the center for several summers with my best friend.

We left Wheeling in 2004 to move to AZ, looking forward to the year round sunshine and hiking and enjoying our "retirement" years.

We have loved having the opportunity to learn about the southwest and to entertain friends from "back home".Source: Patti (Quinn) Greeneltch

With so much in common no one would be surprised to hear we spent many hours talking about the "old days" and generally catching up on what each other had been doing over the past five decades. That took a lot of yakkin'!

One of the interesting tid-bits which surfaced was, during the mid to late 60s, Patti was living in the San Fran bay area near Berkeley at the very same time I was living in the Fillmore District of San Francisco. Small world.

OK. Now that we have the "Quinn Connection" it is time to move on.

When setting up my visit via email Patti had mentioned her husband Ned would be willing to take me to some Indian ruins which were off the beaten track. At the time, I had no idea what this meant, but I soon found out.

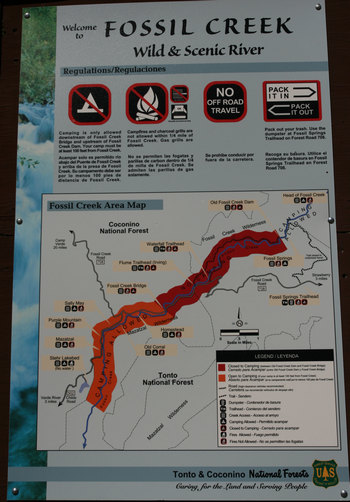

So, on Friday morning we hopped into the "beater" and were off down the road to visit said Indian ruins and see some beautiful countryside. Fossil Creek Road FS #708, which we were on part of the time, will be closed for at least next year due to high traffic volume. Gotta protect them precious resources!

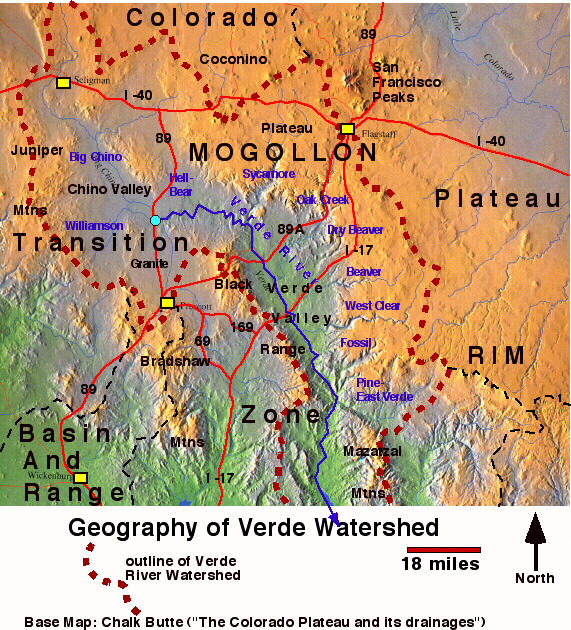

This is the general area where I would be spending the next 3 days.

New territory for me.

(Almost new - but that is another story which involves three young women and camping in the rain.)

Click on the photos below for a larger image.

After quite a few bumpy and dusty miles we arrived at our destination.

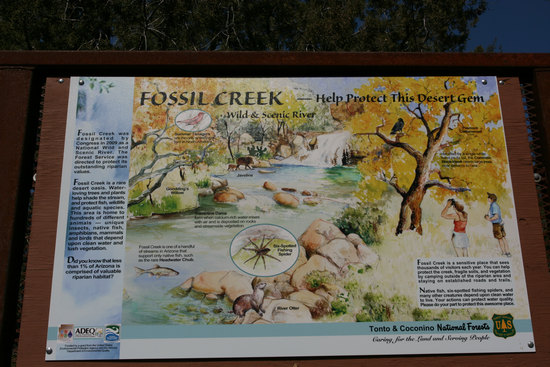

Fossil Creek is a perennial river in central Arizona, located near the community of Strawberry. The headwaters of the creek begin at Fossil Springs, a rare and powerful spring in Arizona, which produces upwards of one million gallons of water per hour.

President Barack Obama signed legislation designating Fossil Creek as a Wild and Scenic River on March 30, 2009, after a long campaign by the Arizona Nature Conservancy.

Source: WikiPedia

Desert Gem indeed. Imagine one million gallons of water per hour flowing through this arid landscape. Truly a linear oasis.

A swimmers delight!

Fossil Creek is part of the Verde River watershed which includes as well as Sycamore Creek where I was soon to go hiking.

Arizona Territory's first governor, John Noble Goodwin, passed through the region in the 1860s, at which time the creek was already known by its present name due to abundant "petrifications" along the stream bed. This rock formation, now known as travertine, is caused by high levels of calcium carbonate in the water, which causes large, fossil-like rock growth. Source: WikiPedia

I can just see Betsy lounging on the rocks and enjoying the view.

As you can imagine with such a water resource there have been many people who settled in the area over the centuries. All of them have left their mark on the landscape including whoever built what is left of this old foundation which is near the creek.

This pipe is part of what remains of a flume built in the early 1900s.

The predictable, steady volume of water in Fossil creek did no go unnoticed by rancher Lew Turner.

The water rights of Fossil Creek, located between Pine/Strawberry and Camp Verde, Arizona, were purchased in 1900 by rancher Lew Turner. His goal was to generate hydroelectric power for sale to mining communities in the Bradshaw Mountains and Black Hills in Yavapai County, such as Jerome, Clarkdale, Crown King and many others.

Arizona Power Company began construction of the Childs power plant in 1908. Because the land around Fossil Creek consists mainly of mountainous terrain and canyons, and the nearest railroad station was located in Mayer, Arizona, more than 400 mules and 600 men were used to pull over 150 wagons along the 40-mile (64 km) wagon trail. Other than the foreman and timekeeper, all of the workers were Apache and Mojave Indians, working for $2 per day. Once construction of the flume began, 120 to 150 feet (46 m) were constructed on a daily basis, costing around $100 per day.

Source: WikiPedia

This is another look at the flume/pipe and what might be part of a valve assembly.

Photo by Ned Greeneltch.

Although these industrial artifacts are interesting and fun to look at, we are here for something a bit older.

The Fossil Creek area,... is a jumble of volcanic rocks — cinder cones, basaltic lavas, pyroclastics, and tuffaceous sediments monopolize the landscape. This area is particularly interesting, because it shows the relationship of the volcanic rocks to others in Verde Valley and in Tonto Basin, a basin just southeast of the area, and because it provides a better understanding of the geologic history of the Basin and Range and Colorado Plateaus Provinces. Source: USGS

And, it was up this "jumble" we were about to climb.

During our ascent we passed many fine specimens of the Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus wislizenii) as well as interesting rock formations.

Here, Ned points out an area on the adjacent slope which might be worth a closer look.

Ned's Creds:

Regional Site Steward Coordinator for the Middle Verde Region of the Red Rock Region which is sponsored by the State Historic Preservation Office.

Site Stewards are volunteers dedicated to protecting and preserving cultural resources and the heritage of Arizona.

The Arizona Site Stewards Program is an organization of volunteers, sponsored by the public land managers of Arizona, whose members are selected, trained and certified by the State Historic Preservation Office and the Governor's Archaeology Advisory Commission. The chief objective of the Stewards Program is to report to the land managers destruction or vandalism of prehistoric and historic archaeological and paleontological sites in Arizona through site monitoring. Stewards are also active in public education and outreach activities.

Source: Arizona State Parks

A nice clump of Hedge Hog cactus nestled in this old, lichen adorned lava.

A closer look at the protective " spines" which are actually modified leaves or bud scales.

This shows the shredded pad of a Beaver-tail cactus which was caused by the munching of a Javelina.

A nice Barrel Cactus nursery and large Beaver-tail (Opuntia spp.) Cactus.

Patti and Ned make their way forward. It was quite the scamble to get to the top.

My first look at pottery sherds.

"You mean we gotta climb up there?"

Patti and nice Barrel Cactus specimen.

This is the top of a Barrel Cactus. Not something you want to accidentally bump into.

Ned told us this was brownware from the rim of a jar.

The Sinagua developed a unique pottery tradition of brown, red, and buff pottery (Alameda Brown Ware), made from local clay and manufactured with a

paddle-and-anvil technique.

The paddle-and-anvil technique is used to flatten and smooth the surface of coiled pots.

Beaver-tail, Agave and Mesquite thrive in the hot, relatively dry volcanic soils

This compares a travertine flake with a smudged brownware sherd. The smudging occurs during the process of firing the pottery.

Ned points out a "purpose shaped rock". It's purpose? Unknown.

Ned determined this is the shoulder of large jar (olla).

The Latin word olla or aulla (also aula) meant a very similar type of pot in Ancient Roman pottery, used for cooking and storage as well as a funerary urn to hold the ashes from

Among Southwestern Native American tribes, ollas used for storing water often were made with narrow necks to prevent evaporation in the desert heat. The olla is used by the Kwaaymii people, among many others, for cooking, storing water, serving meals and even nursing infants.

Because water seeps through the walls of an unglazed olla, these vessels can be used to irrigate plants. The olla is buried in the ground next to the roots of the plant to be irrigated, with the neck of the olla extending above the soil. The olla is filled with water, which gradually seeps into the soil to water the roots of the plant. It is an efficient method, since no water is lost to evaporation or run-off.

A contemporary olla by artist Juan Quezada,

the self-taught originator of Mata Ortiz pottery.The olla is also useful for keeping water cool. When an unglazed olla is filled with water, the water permeates the clay walls of the vessel, causing the olla to “sweat”. The evaporation of the sweat cools the olla and its contents. In the early 20th century, many ranches in the American Southwest used the practice of hanging an olla from a rope on the verandah in a shady, breezy spot. Several hours after the olla was hung, it was cooled enough by evaporation to keep butter and milk safely cold.

Source: WikiPedia

While Patti and Ned kept an eye out for more sherds and other artifacts, I ogled all the beautiful cactus.

Amazing! Gorgeous!

We saw many "bloomed-out" agave as witnessed by this spent flower stalk and the attached dead plant which produced it. Unfortunately, agave kick the bucket once they have flowered. A rather strange adaptation, me thinks.

Another fallen beauty.

Here, Patti and Ned approach the collapsed outer wall of the ruin.

Amongst the jumble of the collapsed outer wall Patti's eagle eye picks up another sherd.

Almost to the top Patti and Ned continue climbing the wallfall.

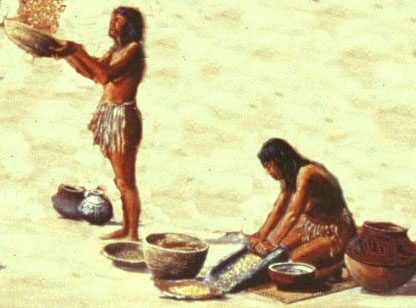

Here, Ned holds a mano once used for grain processing. It was used in conjunction with a metate to grind grain and seeds.

A village woman grinds corn using a mano and metate. Inset from painting by George Nelson, courtesy of the Institute for Texan Cultures.

A metate (or mealing stone) is a mortar, a ground stone tool used for processing grain and seeds. In traditional Mesoamerican culture, metates were typically used by women who would grind calcified maize and other organic materials during food preparation (e.g., making tortillas). Similar artifacts are found all over the world, including China.

While varying in specific morphology, metates adhere to a common shape. They typically consist of large stones with a smooth depression or bowl worn into the upper surface. The bowl is formed by the continual and long-term grinding of materials using a smooth hand-held stone (known as a mano). This action consists of a horizontal grinding motion that differs from the vertical crushing motion used in a mortar and pestle. The depth of the bowl varies, though they are typically not deeper than those of a mortar; deeper metate bowls indicate either a longer period of use or greater degree of activity (i.e., economic specialization).

Another type of metate, called a grinding slab, may also be found among boulder or exposed bedrock outcroppings. The upper face of the stone is used for grinding materials, such as acorns that results in the smoothing of the stone's face and the creation of pocked dimples

Source: WikiPedia

Here Patti sits upon what was either the perimeter wall or room wall.

I tried to find an image that would represent what this pueblo might have looked like and this was the best I could find.

Ned and jumbo Barrel Cactus.

Patti and jumbo Barrel Cactus.

This is the top of the Pueblo ruin.

Pueblo is a term used to describe modern (and ancient) communities of Native Americans in the Southwestern United States of America. The first Spanish explorers of the Southwest used this term to describe the communities housed in apartment-like structures built of stone, adobe mud, and other local material. These structures were usually multi-storeyed buildings surrounding an open plaza. They were occupied by hundreds to thousands of Pueblo people.

Source: WikiPedia

This shows a room damaged by unscrupulous pot hunters.

Another look at the pueblo outer wall.

This shows the remains of the room walls and wallfall.

More wallfall and pot hunter rubble.

Our lunch spot. Sitting on an ancient ruin while having lunch was truly a unique experience for me.

This is the "visitor's pile" or "museum rock" which Ned told me should be discouraged. It would seem just about everyone who finds a sherd likes to prominately place their find so it can be seen and admired by all. Admittedly, I did exactly that and was gently informed any piece picked up should be randomly placed back from whence it came.

A closer look at the visitors pile. Note coin in center for scale.

Perhaps another piece from a olla?

Ned determined this was Awatovi black-on-yellow from Hopi mesas circa 1350 A.D.

Paint Type: Paint is an iron-manganese pigment (Shepard 1971: 182) and varies widely from dense black through a range of reddish and brownish hues. A pale reddish “blush” is present along the edges of painted areas. This coloration, referred to as “bleeding”, is strongest at the edge of the paint and blends outward one to two millimeters into the general surface color (Smith 1971: 477).

Decoration: Designs are clustered and geometric, with a relatively large amount of black paint, relative to the yellow background. Design fields are bordered by banding lines, often present just below the rim, in bowl forms, with a discontinuous segment called the "line break." There are four main layouts, including zonal, radial, meridinoal, and overall layouts. Bowl exteriors: Generally painted with bold, geometrical elements as continuous, angular frets, or of isolated figures. Designs rarely have framing lines but may contain subdivided zones (Smith 1971: 499). Jars: At Awatovi Pueblo, design layouts on jars include are strictly zonal, usually occurring on the vessel body, and framed by wide, circumferential bands that were sometimes broken. The decorated area of the zone is within the framing bands (Smith 1971: 507, 509). On smaller jars, decoration was simpler, consisting of continuous patterns built up of opposed rows of elongated solid triangles with interlocking attached scrolls.

Source: Northern Arizona University - Anthropology Department

A smaller sherd of Awatovi black-on-yellow.

Ned told me this is Hopi yellow ware from the rim of jar.

I believe him! Ned's knowledge about the Pueblo is encyclopedic. And, while "researching" for this write up it gave me a new appreciation of the depth and complexity of Pueblo culture. The more I read the more confused I got! How anyone could sort all this out is beyond me.

Looking off towards the Fossil Creek canyon from atop the perimeter wall. The folks who lived up here had a commanding view and the daunting task of hauling a lot of water up the mountain.

After much discussion, analysis and head-scratching Ned determined this to be a prehistoric bowling ball. And, it may have even been used by Barney Rubble at one time. Nice find, Ned!

Patti queried me about the possible reason for all the damage on the cactus pads. I was clueless at the time, but a little cruising around the web turned up the culprit.

Lesions on pads of prickly pear cacti (Opuntia species) may be caused by several different pests or environmental conditions. However, the most common pad spot on the Engelmann’s prickly pear in the desert of Arizona is caused by a fungus described as a species of Phyllosticta. The disease is found throughout the desert.

Lesions are almost completely black because of the presence of small black reproductive structures called pycnidia produced on the surface of infected plant tissue. Spores produced within these reproductive structures are easily moved by wind blown rain or dripping water and infect new sites on nearby pads. Under moist conditions, the fungus grows within the pad from new infection sites. Pads on the lower part of plants are often most heavily infected since the humidity is higher and moisture often persists after rain. Once pads dry, the fungus becomes inactive and the lesions may fall out or become unattached as the plant tissue heals.

Nearly every pad was infected and it certainly looked beat up.

There were only a few lesions on this nice specimen.

On the way back down from the summit ruin we came across the site of a former garden area. Here Ned spotted this sherd of Black Mesa Black-on-White pottery circa 1200 A.D.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This trip back in time was quite the eye opener for me and gave me much to think about.

Many thanks to both Ned and Patti for a very interesting, informative and fun day.

'Till next time...