Climate change

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The term climate change is used to refer to changes in the Earth's global climate or regional climates. It describes changes in the variability or average state of the atmosphere - or average weather - over any time scale from decades to millions of years. These changes can come from internal processes, be driven by external forces or, most recently, be caused by human activities.

In recent usage, especially in the context of environmental policy, the term "climate change" is often used to refer only to the ongoing changes in modern climate, including the average rise in surface temperature known as global warming. In some cases, the term is also used with a presumption of human causation, including in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The UNFCCC uses "climate variability" for non-human caused variations[1].

For information on temperature measurements over various periods, and the data sources available, see temperature record. For attribution of climate change over the past century, see attribution of recent climate change.

Contents |

Climate change factors

Climate changes reflect variations within the Earth's environment, natural processes going on around it, and the impact of humans. The external factors which can shape climate are often called climate forcings and include such processes as variations in solar radiation, the Earth's orbit, and greenhouse gas concentrations.

Variations within the Earth's climate

Weather, in and of itself, is a chaotic non-linear dynamical system, but in many cases, it is observed that the climate (i.e. the average state of weather) is fairly stable and predictable. This includes the average temperature, amount of precipitation, days of sunlight, and many other variables that might be measured at any given site. However, there are also changes within the Earth's environment that can shape climate.

Glaciation

On moderate time scales, glaciers grow and collapse contributing both to natural variability and greatly amplifying external forces. The most important climate processes of the last several million years are the glacial and interglacial cycles of the present ice age. Though shaped by orbital variations, the internal responses involving continental ice sheets and 130m sea level change certainly played a key role is deciding what climate response would be observed in most regions. Other changes, including Heinrich events, Dansgaard-Oeschger events and the Younger Dryas show the potential for glacial variations to influence climate even in the absence of specific orbital changes.

Ocean variability

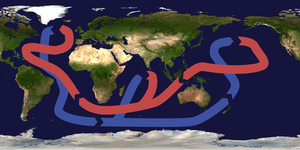

On the scale of mere decades, climate changes can also result from changes within the ocean/atmosphere systems. Many climate states, including the Pacific decadal oscillation, the North Atlantic oscillation, and the Arctic oscillation, have been recognized as modes within the climate system, owing their existence at least in part, to different ways that heat can be stored in the oceans and move between different reservoirs. On longer time scales, ocean processes such as thermohaline circulation play a key role in redistributing heat, and could if changed, dramatically impact climate.

The memory of climate

More generally, most forms of internal variability in the climate system can be recognized as a form of hysteresis meaning that the current state of climate reflects not only the inputs, but also the history of how it got there. For example, a decade of dry conditions may cause lakes to shrink, plains to dry up and deserts to expand. In turn, these conditions may lead to less rainfall in the following years. In short, climate change can be a self-perpetuating process because different aspects of the environment respond at different rates and in different ways to the fluctuations that inevitably occur.

Non-climate factors driving climate

Plate tectonics

On the longest time scales, plate tectonics will reposition continents, shape oceans, build and tear down mountains and generally serve to define the stage upon which climate exists. More recently, plate motions have been implicated in the intensification of the present ice age when approximately ~3 million years ago, the North and South American plates collided to form the Isthmus of Panama and shut off direct mixing between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Solar variation

The sun, as the ultimate source of nearly all energy in the climate system, is an integral part of shaping Earth's climate. On the longest time scales, the sun itself is getting brighter as it continues its main sequence evolution. Early in Earth's history it is thought to have been too cold to support liquid water at the Earth's surface, leading to what is known as the faint young sun paradox.

On more modern time scales, there are also a variety of forms of solar variation, including the 11-year solar cycle, and longer term modulations. These variations are considered to be influential in triggering the Little Ice Age and for much of the warming observed from 1900 to 1950.

Orbital variations

In their impact on climate, orbital variations are in some sense an extension of solar variability, because slight variations in the Earth's orbit lead to changes in the distribution and abundance of sunlight reaching the Earth surface. Such orbital variations, known as Milankovitch cycles, are a highly predictable consequence of basic physics due to the mutual interactions of the Earth, its moon, and the other planets. These variations are considered the driving factors underlying the glacial and interglacial cycles of the present ice age. Subtler variations are also present, such as the repeated advance and retreat of the Sahara desert in response to orbital precession.

Magnetic Field Change

Volcanism

A single eruption of the kind that occurs several times per century can significantly impact climate for a period of a few years. Huge eruptions, known large igneous provinces, occur only a few times every hundred million years, but can reshape climate for millions of years and cause mass extinctions.

Greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gases are one of the key forces in the global warming discussion, they also have been important to the understanding of Earth's climate history. The greenhouse effect, which is the warming produced as greenhouse gases trap heat, plays a key and necessary role in regulating Earth's temperature.

Over the last 600 million years, carbon dioxide concentrations have varied from perhaps >5000 ppm to less than 200 ppm, due primarily to the impact of geological processes and biological innovations. Curiously, it has been argued (Veizer et al. 1999) that variations in greenhouse gas concentrations have not been well correlated to climate change, with perhaps plate tectonics playing a more dominant role. However there are several examples of rapid changes in the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the Earth's atmosphere that do appear to have led to strong warming, including the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, the Permian-Triassic extinction event, and the end of the Varangian snowball earth event.

During the modern era, rising carbon dioxide levels are implicated as the primary cause to global warming since 1950.

Human influences

Anthropogenic factors are acts by humans that change the environment and influence climate. The biggest factor of present concern is increases in CO2 levels due to emission from fossil fuel combustion, but other factors, including land use, ozone depletion, and deforestation also impact climate.

Fossil fuels

Beginning with the industrial revolution in the 1850s and accelerating ever since, the human consumption of fossil fuels has elevated CO2 levels from a concetration of ~280 ppm to more than 370 ppm today. These increases are projected to reach more than 560 ppm before the end of the next century. Along with rising methane levels, these changes are anticipated to cause a increase of 1.4-5.6 °C between 1990 and 2100.

Land use

Prior to widespread fossil fuel use, humanity's largest impact on local climate is likely to have resulted from land use. Irrigation, deforestation, and agriculture fundamentally change the environment. For example, they change the amount of water going into and out of a given locale. They also may change the local albedo by influencing the ground cover and impacting the amount of sunlight which is absorbed. For example, there is evidence to suggest that the climate of Greece and other Mediterranean countries was permanently changed by widespread deforestation between 700 BC and 0 BC (the wood being used for ship-building, construction and fuel purposes), with the result that the modern climate in the region is significantly hotter and drier and the species of trees which were used for ship-building in the ancient world can no longer be found in the area.

A controversial hypothesis by William Ruddiman suggests that the rise of agriculture and the accompanying deforestation led to the increases in carbon dioxide and methane during the period 5000-8000 years ago. These increases, which reversed previous declines, may have been responsible for delaying the onset of the next glacial period, according to Ruddimann's hypothesis.

Interplay of factors

If a certain forcing (for example, solar variation) acts to change the climate, then there may be mechanisms which act to amplify or reduce the effects. These are called positive and negative feedbacks. As far as is known, the climate system is generally stable with respect to these feedbacks: positive feedbacks do not "runaway". Part of the reason for this is the existence of a powerful negative feedback between temperature and emitted radiation, which increases as the fourth power of absolute temperature.

However, a number of important feedbacks do exist. The glacial and interglacial cycles of the present ice age provide an important example. It is believed that orbital variations provide the timing for the growth and retreat of ice sheets. However, the ice sheets themselves reflect sunlight back into space and hence promote cooling and their own growth, known as the ice-albedo feedback. Further, falling sea levels and expanding ice decrease plant growth and indirectly lead to declines in carbon dioxide and methane. This leads to further cooling.

Similarly, rising temperatures caused, for example, by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases could lead to retreating snow lines, revealing darker ground underneath, and consequently absorbing more sunlight.

Water vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide can also act as significant positive feedbacks, their levels rising in response to a warming trend, thereby accelerating that trend. Water vapor acts strictly as a feedback (excepting small amounts in the stratosphere), unlike the other major greenhouse gases, which can also act as forcings.

More complex feedbacks involve the possibility of changing circulation patterns in the ocean or atmosphere. For example, a significant concern in the modern case is that melting glacial ice from Greenland will interfere with sinking waters in the North Atlantic and inhibit thermohaline circulation. This could affect the Gulf Stream and the distribution of heat to Europe and the east coast of the United States .

Other potential feedbacks are not well understood and may either inhibit or promote warming. For example, it is unclear whether rising temperature promote or inhibit vegetative growth which could in turn draw down either more or less carbon dioxide. Similarly, increasing temperatures, may lead to either more or less cloud cover [2]. Since on the balance cloud cover has a strong cooling effect, any change to the abundance of clouds also impacts climate.

For additional discussion of feedbacks relevant to ongoing climate change, see here: [3].

Examples of climate change

Climate change has continued of through out the entire history of Earth. In addition to modern observations of climate, the field of paleoclimatology has provided information of climate change in the ancient past. Obviously, most of these changes are solely the result natural factors.

- Climate of the deep past

- Climate of the last 500 million years

- Climate of recent glaciations

- Recent climate

References

- The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago, Ruddiman WF; Climatic Change, 61 (3): 261-293 Dec 2003

- A test of the overdue-glaciation hypothesis, William F. Ruddiman, Stephen J. Vavrus, John E. Kutzbach, Quaternary Science Reviews 24 (2005) 11

- A note on the relationship between ice core methane concentrations and insolation, Schmidt, GA, Shindel, DT and Harder, S; GRL v31 L23206, 16 December 2004.

- William F. Ruddiman (2005), Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum:How Humans Took Control of Climate, Princeton University Press

- What effects are we seeing now and what is still to come?Calvin Jones "Climate Change: Facts and Impacts"

See also

- Abrupt climate change

- Action on Climate Change

- Climate model

- Global warming

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- Mitigation of global warming

- Paleoclimatology

- Sea level change

- Temperature record

- United Kingdom Climate Change Programme

- UNFCCC

External links

- Paleoclimateology from a 1995 Report from the American Geophysical Union

- A Brief Introduction to History of Climate, an excellent overview by Prof. Richard A. Muller of UC Berkeley.

- Global Change Master Directory: A directory of Earth science data

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

- 2001 Reports on the Climate Change by the IPCC.

- A summary of the IPCC report by GreenFacts.

- Open Democracy Climate Change debate Article series by scientists, activists and others, and global debate on the politics

- Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, Norwich, UK

- Climate Change Chronicles The latest news and information on climate change, alternative energy, global warming and energy efficiency from around the internet

- Climate change, a brief review An overview of climate change, theories and perspectives, and notable weather patterns.

- Guardian Unlimited - Special Report: Climate Change ongoing coverage by Guardian Unlimited

- RealClimate » Climate Science RealClimate is a commentary site on climate science by working climate scientists for the interested public and journalists.

- ClimateArk a Climate Change Portal and Search Engine dedicated to promoting public policy that addresses global climate change through reductions in carbon dioxide and other emissions, renewable energy, energy conservation and ending deforestation.

- Climate Change Campaigning and Writing Climate Change Action is written to educate, and to provide resources for lifestyle changes as well as political action.