Industrial Revolution

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The Industrial Revolution was the major technological, socioeconomic and cultural change in the late 18th and early 19th century resulting from the replacement of an economy based on manual labor to one dominated by industry and machine manufacture. It began in England with the introduction of steam power (fueled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing). The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the nineteenth century enabled the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries.

The dating of the Industrial Revolution is not exact, but T.S. Ashton held it covers roughly 1760-1830, in effect the reigns of George III, The Regency, and part of William IV. There was no cut-off point for it merged into the Second Industrial Revolution from about 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steam-powered ships, and railways, and later in the nineteenth century the growth of the internal combustion engine and the development of electrical power generation.

The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America, eventually affecting the rest of the world. The impact of this change on society was enormous and is often compared to the Neolithic revolution, when mankind developed agriculture and gave up its nomadic lifestyle.

The term industrial revolution was introduced by Friedrich Engels and Louis-Auguste Blanqui in the second half of the 19th century.

Contents |

Causes

The causes of the Industrial Revolution were complex and remain a topic for debate, with some historians seeing the Revolution as an outgrowth of social and institutional changes wrought by the end of feudalism in Great Britain after the English Civil War in the 17th century. The Enclosure movement and the British Agricultural Revolution made food production more efficient and less labor-intensive, forcing the surplus population who could no longer find employment in agriculture into cottage industry, such as weaving, and in the longer term into the cities and the newly-developed factories. The colonial expansion of the 17th century with the accompanying development of international trade, creation of financial markets and accumulation of capital are also cited as factors, as is the scientific revolution of the 17th century. Technological innovation was another important factor, in particular the new invention and development of the steam engine during the 18th century.

The presence of a large domestic market should also be considered an important catalyst of the Industrial Revolution, particularly explaining why it occurred in Britain. In other nations, such as France, markets were split up by local regions, which often imposed tolls and tariffs on goods traded among them.

Why Europe?

One question of active interest to historians is why the Industrial Revolution occurred in Europe and not other parts of the world, particularly China. Numerous factors have been suggested, including ecology, government, and culture. Benjamin Elman argues that China was in a high level equilibrium trap in which the nonindustrial methods were efficient enough to prevent use of industrial methods with high costs of capital. Kenneth Pomeranz, in the Great Divergence, argues that Europe and China were remarkably similar in 1700, and that the crucial differences which created the Industrial Revolution in Europe were: sources of coal near manufacturing centres and raw materials such as food and wood from the New World, which allowed Europe to expand economically in a way that China could not. Indeed, a combination of all of these factors is possible.

Why did it start in Great Britain?

The debate about the start of the Industrial Revolution also concerns the lead of 30 to 100 years that Britain had over other countries. Some have stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that the United Kingdom received from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment.

Alternatively, the greater liberalisation of trade from a large merchant base may have allowed Britain to utilise emerging scientific and technological developments more effectively than countries with stronger monarchies, such as China and Russia. Great Britain emerged from the Napoleonic Wars as the only European nation not ravaged by financial plunder and economic collapse, and possessing the only merchant fleet of any useful size (European merchant fleets having been destroyed during the war by the Royal Navy). The United Kingdom's extensive exporting cottage industries also ensured markets were already available for many early forms of manufactured goods. The nature of conflict in the period resulted in most British warfare being conducted overseas, reducing the devastating effects of territorial conquest that affected much of Europe. This was further aided by Britain's geographical position— an island separated from the rest of mainland Europe.

Another theory is that Great Britain was able to succeed in the Industrial Revolution due to the availability of key resources it possessed. It had a dense population for its small geographical size. Enclosure of common land and the related Agricultural revolution made a supply of this labour readily available. There was also a local coincidence of natural resources in the North of England, the English Midlands, South Wales and the Scottish Lowlands. Local supplies of coal, iron, lead, copper, tin, limestone and water power, resulted in excellent conditions for the development and expansion of industry.

The stable political situation in Great Britain from around 1688, and British society's greater receptiveness to change (when compared with other European countries) can also be said to be factors favouring the Industrial Revolution.

Protestant work ethic

Another theory is that the British advance was due to the presence of an entrepreneurial class which believed in progress, technology and hard work.1 The existence of this class is often linked to the Protestant work ethic and the particular status of dissenting Protestant sects, such as the Quakers, Baptists and Presbyterians that had flourished with the English Civil War. Reinforcement of confidence in the rule of law, which followed the establishment of the prototype of constitutional monarchy in Great Britain in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the emergence of a stable financial market there based on the management of the national debt by the Bank of England, contributed to the capacity for, and interest in, private financial investment in industrial ventures.

Dissenters found themselves barred or discouraged from almost all public offices as well as University education at Oxford and Cambridge, when the restoration of the monarchy took place and membership in the official Anglican church became mandatory due to the Test Act. They became active in banking, manufacturing and the Unitarians in particular, were much involved in education by running Dissenting Academies, where, in contrast to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and schools such as Eton and Harrow, much attention was given to mathematics and the sciences - area of scholarship vital to the development of manufacturing technologies.

Historians sometimes consider this social factor to be extremely important, along with the nature of the national economies involved. While members of these sects were excluded from certain circles of the government, they were considered as fellow Protestants, to a limited extent, by many in the middle class, such as traditional financiers or other businessmen. Given this relative tolerance and the supply of capital, the natural outlet for the more enterprising members of these sects would be to seek new opportunities in the technologies created in the wake of the Scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Criticism of the Calvinism hypothesis

This argument has, on the whole, tended to neglect the fact that several inventors and entrepreneurs were rational free thinkers or "Philosophers" typical of a certain class of British intellectuals in the late 18th century, and were by no means normal church goers or members of religious sects. Examples of these free thinkers were the Lunar Society of Birmingham (which flourished from 1765 to 1809). Its members were exceptional in that they were among the very few who were conscious that an industrial revolution was then taking place in Great Britain. They actively worked as a group to encourage it, not least by investing in it and conducting scientific experiments which led to innovative products.

Innovations

The invention of the steam engine was the most important innovation of the industrial revolution. This was made possible by earlier improvements in iron smelting and metal working based on the use of coke rather than charcoal. Earlier in the 18th century the textile industry had harnessed water power to drive improved spinning machines (see spinning jenny) and looms (see flying shuttle). These textile mills became the model for the organization of human labour in factories.

Transmission of innovation

Knowledge of new innovation was spread by several means. Workers who were trained in the technique might move to another employer, or might be poached. A common method was for someone to make a study tour, gathering information where he could. Today this is called industrial espionage, with modern concepts of automatic illegality.

During the whole of the Industrial Revolution and for the century before, all European countries and America engaged in this manner of study-touring; some nations, like Sweden and France, trained civil servants or technicians to undertake it as a matter of state policy. In other countries, notably Britain and America, this practice was carried out by individual manufacturers anxious to improve their own methods. Study tours were common then, as was the keeping of travel diaries; writings made by industrialists and technicians of the period are an incomparable source of information about their methods.

Another means for the spread of innovation was by the network of informal philosophical societies like the Lunar Society of Birmingham, in which members met to discuss science and often its application to manufacturing. Some of these societies published volumes of proceedings and transactions, and the London-based Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce or, more commonly, Society of Arts published an illustrated volume of new inventions, as well as papers about them in its annual Transactions.

There were publications describing technology. Encyclopaedias such as Harris's Lexicon technicum (1704) and Dr Abraham Rees's Cyclopaedia (1802-1819) contain much of value. Rees's Cyclopaedia contains an enormous amount of information about the science and technology of the first half of the Industrial Revolution, very well illustrated by fine engravings. Foreign printed sources such as the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers and Diderot's Encyclopédie explained foreign methods with fine engraved plates.

Periodical publications about manufacturing and technology began to appear in the last decade of the 18th century, and a number regularly included notice of the latest patents. Foreign periodicals such as the Annales des Mines published accounts of travels made by French engineers who observed British methods on study tours.

Factories

Industrialisation also led to the creation of the factory. John Lombe's water-powered silk mill at Derby was operational by 1721. In 1746 an integrated brass mill was working at Warmley near Bristol. Raw material went in at one end, was smelted into brass, and was turned into pans, pins, wire, and other goods. Housing was provided for workers on-site.

Josiah Wedgwood and Matthew Boulton were other prominent early industrialists.

The factory system was largely responsible for the rise of the modern city, as workers migrated into the cities in search of employment in the factories. For much of the 19th century, production was done in small mills, which were typically powered by water and built to serve local needs.

The transition to industrialization was not wholly smooth. For example, a group of English workers known as Luddites formed to protest against industrialization and sometimes sabotaged factories.

One of the earliest reformers of factory conditions was Robert Owen.

Machine tools

The Industrial Revolution could not have developed without machine tools, for they enabled manufacturing machines to be made. They have their origins in the tools developed in the 18th century by makers of clocks and watches, and scientific instrument makers to enable them to batch-produce small mechanisms. The mechanical parts of early textile machines were sometimes called 'clock work' due to the metal spindles and gears they incorporated. The manufacture of textile machines drew craftsmen from these trades and is the origin of the modern engineering industry. Machine makers early developed special purpose machines for making parts.

Machines were built by various craftsmen. Carpenters for making the wooden framing, and smith and the turner for the metal parts. Because of the difficulty of manipulating metal, and the lack of machine tools, metal was reduced to a minimum. Wood framing had the disadvantage of changing dimensions with temperature and humidity, and the various joints used tended to rack (work loose) over time. As the Industrial Revolution progressed, machines with metal frames became more common, but required machine tools to make them economically. Before the advent of machine tools metal was worked manually using the basic hand tools of hammers, files, scrapers, saws and chisels. Small metal parts were readily made by this means, but for large machine parts, such as castings for a lathe bed, where components had to slide together, the production of flat surfaces by means of the hammer and chisel followed by filing, scraping and perhaps grinding with emery paste, was very laborious and costly.

Apart from workshop lathes used by craftsmen, the first large machine tool was the cylinder boring machine, used for boring the large-diameter cylinders on early steam engines. They were to be found at all steam-engine manufacturers. The planing machine, the slotting machine and the shaping machine were developed in the first decades of the 19th century. Although the milling machine was invented at this time, it was not developed as a serious workshop tool until during the Second Industrial Revolution.

Military production had a hand in their development. Henry Maudslay, who trained a school of machine-tool makers early in the 19th century, was employed at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, as a lad where he would have seen the large horse-driven wooden machines for cannon boring made and worked by the Verbruggans. He later worked for Joseph Bramah on the production of metal locks, and soon after he began working on his own account was engaged to build the machinery for making ships' pulley blocks for the Royal Navy in the Portsmouth Block Mills. These were all metal, and the first machines for mass production and making components with a degree of interchangeability. The lessons Maudslay learned about the need for stability and precision he adapted to the development of machine tools, and in his workshops he trained a generation of men to build on his work, such as Richard Roberts, Joseph Clement and Joseph Whitworth.

Maudslay made his name for his lathes and precision measurement. James Fox of Derby had a healthy export trade in machine tools for the first third of the century, as did Matthew Murray of Leeds. Roberts made his name as a maker of high-quality machine tools, and as a pioneer of the use of jigs and gauges for precision workshop measurement.

Textile manufacture

- See main article Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution

In the early 18th century, British textile manufacture was based on wool which was processed by individual artisans, doing the spinning and weaving on their own premises. This system is called a cottage industry. Flax and cotton were also used for fine materials, but the processing was difficult because of the pre-processing needed, and thus goods in these materials made only a small proportion of the output.

Use of the spinning wheel and hand loom restricted the production capacity of the industry, but a number of incremental advances increased productivity to the extent that manufactured cotton goods became the dominant British export by the early decades of the 19th century. India was displaced as the premier supplier of cotton goods.

Step by step, individual inventors increased the efficiency of the individual steps of spinning (carding, twisting and spinning, and subsequently rolling) so that the supply of yarn fed a weaving industry that itself was advancing with improvements to shuttles and the loom or 'frame'. The output of an individual labourer increased dramatically, with the effect that these new machines were seen as a threat to employment, and early innovators were attacked and their inventions wrecked. The inventors often failed to exploit their inventions, and fell on hard times.

To capitalize upon these advances it took a class of entrepreneurs, of which the most famous is Richard Arkwright. He is credited with a list of inventions, but these were actually developed by people such as Thomas Highs and John Kay; Arkwright nurtured the inventors, patented the ideas, financed the initiatives, and protected the machines. He created the cotton mill which brought the production processes together in a factory, and he developed the use of power – first horse power, then water power and finally steam power – which made cotton manufacture a mechanised industry.

Mining

Coal mining in Britain is of great age. Before the steam engine, pits were often shallow bell pits, following a seam of coal along the surface and being abandoned as the coal was extracted. In other cases, if the geology was favourable, the coal was mined by means of an adit driven into the side of a hill. Shaft mining was done in some areas, but the limiting factor was the problem of removing water. It could be done by hauling buckets of water up the shaft by means of a horse gin, or it could be drained by an adit leading to a stream or ditch at lower level where it could flow away by gravity. A number of historic mining areas of Britain, such as the Kingswood coalfield near Bristol, still have adits running to this day, as of 2005, almost a century after the industry ceased. The introduction of the steam engine enabled shafts to be made deeper, hence increasing output.

Metallurgy

- See main article Metallurgy during the Industrial Revolution

In the early 18th century, small-scale iron working and extraction and processing of other metals were carried out where local resources permitted. Fuel was primarily wood in the form of charcoal, but consumption was starting to be constrained by lack of available timber. At the same time, demand for high-quality iron was dramatically increasing to keep pace with the improvements in military technology and the involvement of Britain in numerous European wars.

Principal suppliers of high-quality iron goods were Sweden and Russia, with Russia being able to command increasingly high prices as Britain's need grew.

To fuel the iron smelting process, people moved from wood to coal and coke. Production of pig iron, cast iron and wrought iron improved through the exchange of ideas (although this was by no means a fast process), with the most well-known name being Abraham Darby. The first Abraham Darby made great strides with using coke to fuel his blast furnaces at Coalbrookdale (1709), although this was principally due to the nature of the coke he was using, and the scientific reasons for the improvement were only discovered later. His family followed in his footsteps, and iron became a major construction material.

Other improvements followed, with Benjamin Huntsman developing a crucible steel technique in the 1740s, and Henry Cort's puddling furnace enabling large-scale production of wrought iron to take place.

The reliance on overseas supplies was diminished, and improvements in machine tools and the use of iron and steel in the development of the railways further boosted the industrial growth of Great Britain.

Steam power

- See main article Steam power during the Industrial Revolution

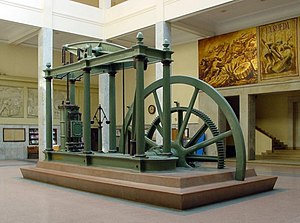

The stationary steam engine had great influence on the progress of the Industrial Revolution, but for all of it many industries still relied on wind and water power as well as horse and man-power for driving small machines.

The steam engine was first used for draining mines or for driving mills by pumping water back to a reservoir that had passed through a water wheel. James Watt's invention of rotary motion in the 1780s enabled a steam engine to drive a factory or mill directly.

Until about 1800, the most common pattern of steam engine was the beam engine, which was built within a stone or brick engine-house but after then various patterns of portable (ie readily removable engines, not on wheels) were developed, such as the table engine. The development of machine tools such as the planing and shaping machine enabled all the metal parts of the engines to be easily and accurately cut. Engines could be made in varying sizes and patterns to suit various requirements, such as for locomotives and steam boats.

Transportation

- See main article Transport during the Industrial Revolution

At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, inland transport was by navigable rivers and roads, with coastwise vessels employed to move heavy goods by sea. Railways or waggon ways were used for conveying coal to rivers for further shipment, and canals were beginning to be cut for moving goods between larger towns and cities.

During the Industrial Revolution, these different methods were improved and developed.

Navigable rivers

See main article Rivers of Great Britain

All the major rivers were made navigable to a great or lesser degree. The Severn in particular was used for the movement of goods to the Midlands which had been imported into Bristol from abroad, and the export of goods from centres of production in Shropshire such as iron goods from Coalbrookdale. Transport was by way of Trows - small sailing vessels which could pass the various shallows and bridges in the river. These could navigate the Bristol Channel to the South Wales ports and Somerset ports, such as Bridgwater and even as far as France.

Roads

Much of the original British road system was poorly maintained by thousands of local parishes, but from the 1760s turnpike trusts were set up to charge tolls and maintain some roads. New engineered roads were built by Metcalf, Telford and Macadam. The major turnpikes radiated from London and were the means by which the Royal Mail was able to reach the rest of the country. Heavy goods transport on these roads was by means of slow broad wheeled carts hauled by teams of horses. Lighter goods were conveyed by smaller carts or by teams of pack horses. Stage coaches transported rich people. The less wealthy walked or paid to ride on a carriers cart.

Coastal sail

Sailing vessels had long been used for moving goods round the British coast. The trade transporting coal to London from Newcastle had begun in medieval times. The major international seaports such as London, Bristol and Liverpool were the means by which raw materials such as cotton might be imported and finished goods exported. Transporting goods onwards within Britain by sea was common during the whole of the Industrial Revolution and only fell away with the growth of the railways at the end of the period.

Canals

See main article History of the British canal system

Canals began to be built in the late eighteenth century to link the major manufacturing centres in the midlands and north with seaports and with London, at that time the largest manufacturing centre in the country. Canals were the first technology to allow bulk materials to be easily transported across county. A single canal horse could pull a load dozens of times larger than a cart at a faster pace. By the 1820s a national network was in existence. Canal construction served as a model for the organisation and methods later used to construct the railways. They were eventually largely superseded as profitable commercial enterprises by the spread of the railways from the 1840s on.

Britain's canal network, together with its surviving mill buildings, is one of the most enduring features of the early Industrial Revolution to be seen in Britain.

Railways

See main article History of rail transport in Great Britain

Wagonways for moving coal in the mining areas had started in the 17th century, and were often associatad with canal or river systems for the further movement of coal. These were all horse drawn or relied on gravity, with a stationary steam engine to haul the wagons back to the top of the incline. The first applications of the steam locomotive were on waggon or plate ways (as they were then often called from the cast iron plates used). Horse-drawn public railways did not begin until the early years of the 19th century. Steam-hauled public railways began with the Liverpool and Manchester and Stockton and Darlington Railways of the late 1820s. The construction of major railways connecting the larger cities and towns began in the 1830s but only gained momentum at the very end of the Industrial Revolution.

Social problems

The industrial revolution lead to a number of social problems within the newly developed working class. Children worked under miserable conditions and the families lived in bad housing.

Child labour

Child labor existed before the Industrial Revolution, and in fact dates back to prehistoric times, but during the Industrial Revolution it grew far more abusive than ever before.[1] Politicians tried to limit child labour by law. Factory owners resisted -- they felt that they were aiding the poor by giving their children work from the age of five years onward. In 1833 the first law against child labour, the Factory Act of 1833, was passed in England: Children younger than nine were not allowed to work, children were not permitted to work at night and the work day of youth under the age of 18 was limited to twelve hours. Factory inspectors supervised the execution of this law. About ten years later, the employment of children and women in mining was forbidden. These laws improved the situation; however child labour remained a problem in Europe up to the 20th century.

Housing situation

In 1832 James Phillips Kay, an Edinburgh doctor, published a detailed report on the working conditions of the poor and describes worker's housing establishments as follows:

- Here, without distinction of age or sex, careless of all decency, they are crowded in small and wretched apartments; the same bed receiving a succession of tenants until too offensive for their unfastidious senses. 3

In 1842 a Sanitary Report was produced by Edwin Chadwick:

- "In a cellar in Pendleton, I recollect there were three beds in the two apartments of which the habitation consisted, but having no door between them, in one of which a man and his wife slept; in another, a man, his wife and child; and in a third two unmarried females.(...)I have met with upwards of 40 persons sleeping in the same room, married and single, including, of course, children and several young adult persons of either sex."

Luddites

- Main article: Luddite

The rapid industrialization of the English economy cost many craft workers their jobs. The textile industry in particular industrialized early, and many weavers found themselves suddenly unemployed since they could no longer compete with machines which only required relatively limited (and unskilled) labor to produce more cloth than a single weaver. Many such unemployed workers, weavers and others, turned their animousity towards the machines that had taken their jobs and began destroying factories and machinery. These attackers became known as Luddites, supposedly followers of Ned Ludd, a folklore figure. The first attacks of the Luddite movement began in 1811. The Luddites rapidly gained popularity, and the British government had to take drastic measures to protect industry.

Organization of labour

- See also Labour history

In England the Combination Act forbade workers to form any kind of trade union from 1799 until its repeal in 1824. After this unions were still severely restricted.

In 1842 Cotton Workers in England staged a widespread strike. Conditions for the working class were so bad during the industrial revolution, unions were formed to help protect the rights of the working man. The main method the unions used to effect change was strike action. Strikes were painful events for both sides, the unions and the management. The management was upset because strikes took their precious working force away for a large period of time, and the unions had to deal with riot police and various middle class prejudices that striking workers were the same as criminals, as well as loss of income. The strikes often led to violent and bloody clashes between police and workers. Factory managers usually reluctantly gave in to various demands made by strikers, but the conflict was generally long.

Effects

The application of steam power to the industrial processes of printing supported a massive expansion of newspaper and popular book publishing, which reinforced rising literacy and demands for mass political participation. Universal white male suffrage was adopted in the United States, resulting in the election of the popular Andrew Jackson in 1828 and the creation of political parties organized for mass participation in elections. In the United Kingdom, the Reform Act 1832 addressed the concentration of population in districts with almost no representation in Parliament, expanding the electorate, leading to the founding of modern political parties and initiating a series of reforms which would continue into the 20th century. In France, the July Revolution widened the franchise and established a constitutional monarchy. Belgium established its independence from the Netherlands, as a constitutional monarchy, in 1830. Struggles for liberal reforms in Switzerland's various cantons in the 1830s had mixed results. A further series of attempts at political reform or revolution would sweep Europe in 1848, with mixed results, and initiated massive migration to North America, as well as parts of South America, South Africa, and Australia. The mass migration of rural families into urban areas saw the growth of bad living conditions in cities, long work hours without the traditional agricultural breaks (such as after harvest or in mid winter), a rise in child labour (the children received less pay and benefits than adults) and the rise of nationalism in most of Europe. The increase in coal usage saw a massive increase in atmospheric pollution.

The Industrial Revolution had significant impacts on the structure of society. Prior to its rise, the public and private spheres held strong overlaps; work was often conducted through the home, and thus was shared in many cases by both a wife and her husband. However, during this period the two began to separate, with work and home life considered quite distinct from one another. This shift made it necessary for one partner to maintain the home and care for children. Women, holding the distinction of being able to breastfeed, thus more often maintained the home, with men making up a sizeable fraction of the workforce. With much of the family income coming from men, then, their power in relation to women increased further, with the latter often dependent on men's income. This had enormous impacts on the defining of gender roles and was effectively the model for what was later termed the traditional family.

However, the need for a large workforce also pressured many women into industrial work, where they were often paid much less in relation to men. This was in large part due to a lack of organized labor among women to push for benefits and wage increases, and in part to ensure women's continued dependence on a man's income to survive.

Intellectual paradigms

Capitalist

The advent of The Enlightenment provided an intellectual framework which welcomed the practical application of the growing body of scientific knowledge — a factor evidenced in the systematic development of the steam engine, guided by scientific analysis, and the development of the political and sociological analyses, culminating in Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.

Criticism

Marxism

Karl Marx saw the industrialization process as the logical dialectical progression of feudal economic modes, necessary for the full development of capitalism, which he saw as in itself a necessary precursor to the development of socialism and eventually communism. According to Marx, industrialization engenders the polarization of societies into two classes, the bourgeoisie — those who own the means of production, i.e. the factories and the land, and the much larger proletariat — the working class who actually perform the labor necessary to extract something valuable from the means of production. Marx asserts that the relationship between the two classes is fundamentally parasitic, insofar as the proletariat are always undercompensated for the true value of their labor by the bourgeoisie (according to the labor theory of value), which allows the bourgeoisie to grow absurdly wealthy through nothing more than the wholesale exploitation of the proletarians' labor.

Rapid advancements in technology left many skilled workers unemployed, as one agricultural and manufacturing task after another was mechanized. The flight of millions of newly unemployed people from rural areas or small towns to the large cities, and thus the development of large urban population centers, led to unprecedented conditions of poverty in the slums that housed workers for the new factories. At the same time, the bourgeois class, at only a small fraction of the proletariat's size, became exceedingly wealthy.

Marx says that the industrial proletariat will eventually develop class consciousness and revolt against the bourgeois, leading to a more egalitarian socialist and eventually Communist state where the workers themselves own the means of industrial production. See Marxism.

Romantic Movement

See main article Romantic movement

From 1800 on, there was a great deal of intellectual hostility towards industrialisation by the Romantic Movement with its major exponent William Blake.

The Second Industrial Revolution

- Main article: Second Industrial Revolution

The insatiable demand of the railroads for more durable rail led to the development of the means to cheaply mass-produce steel. Steel is often cited as the first of several new areas for industrial mass-production, which are said to characterize a "Second Industrial Revolution", beginning around 1850. This "second" Industrial Revolution gradually grew to include the chemical industries, petroleum refining and distribution, electrical industries, and, in the twentieth century, the automotive industries, and was marked by a transition of technological leadership from Great Britain to the United States and Germany.

The introduction of hydroelectric power generation in the Alps enabled the rapid industrialization of coal-starved northern Italy, beginning in the 1890s. The increasing availability of economic petroleum products also reduced the relation of coal to the potential for industrialization.

By the 1890s, industrialization in these areas had created the first giant industrial corporations with often nearly global international operations and interests, as companies like U.S. Steel, General Electric, and Bayer AG joined the railroads on the world's stock markets and among huge, bureaucratic organizations.

Notes

1 The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber, (1904-1905, Eng. trans. 1930)

2 In Praise of Idleness, Bertrand Russell

3 The full text of the report published by James Phillips Kay in 1832

References

General

- Bernal, John Desmond. Science and Industry in the Nineteenth Century Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970.

- Derry, Thomas Kingston and Trevor I. Williams. A Short History of Technology : From the Earliest Times to A.D. 1900 New York : Dover Publications, 1993.

- Hobsbawm, Eric J.. Industry and Empire : From 1750 to the Present Day . New York : New Press ; Distributed by W.W. Norton,1999.

- Kranzberg, Melvin and Carroll W. Pursell, Jr. editors. Technology in Western civilization New York, Oxford University Press, 1967.

- Lines, Clifford, Companion to the Industrial Revolution, London, New York etc., Facts on File, 1990, ISBN 0-8160-2157-0

Causes

- Landes, David S. The Unbound Prometheus : Technical Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present 2nd ed. New York : Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Paul Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century, First English translation 1928, revised and reset edition 1961.

Machine tools

- Norman Atkinson Sir Joseph Whitworth,1996, Sutton Publishing Limited 1996 ISBN 0-7509-1211-1 (hc), ISBN 0-7509-1648-6 (pb)

- John Cantrell and Gillian Cookson, eds., Henry Maudslay and the Pioneers of the Machine Age, 2002, Tempus Publishing, Ltd, pb., (ISBN 0-7524-2766-0)

- Rev. Dr. Richard L. Hills, Life and Inventions of Richard Roberts, 1789-1864, Landmark Publishing Ltd, 2002, (ISBN 1-84306-027-2)

- Joseph Wickham Roe, English and American Tool Builders, Yale University Press, 1916. Rep. Lindsay Publications Inc., Bradley IL.,1987, (ISBN 0-917914-74-0),(cloth), (ISBN 0-9107914-73-2), paper.

See Also

External links

- Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Industrial Revolution

- BBC History Home Page: Industrial Revolution

- National Museum of Science and Industry website: machines and personalities