Execution by burning

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

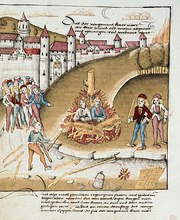

Execution by burning is capital punishment by fire. It has a long history as a method of punishment for crimes such as treason and for other unpopular acts such as heresy and the practice of witchcraft. For a number of reasons, this method of execution fell into disfavor among governments. The particular form of execution by burning in which the condemned is bound to a large stake is more commonly called burning at the stake.

Contents |

Cause of death

If the fire is large (for instance, when a large number of prisoners were executed at the same time), death often came from the carbon monoxide poisoning before flames actually caused harm to the body. However, if the fire is small, the convict burns for a few minutes in pain until death from heatstroke or loss of blood plasma. Typically, the executioner would arrange a pile of wood around the condemned's feet and calves, with supplementary small bundles of sticks and straw called faggots at strategic intervals up his/her body.

When applied with skillful cruelty, the victim's skin would burn progressively in the sequence: calves, thighs and hands, torso and forearms, breasts, upper chest, face; and then finally death. On other occasions, people died from suffocation with only their calves in fire. In many burnings a rope was attached to the convict's neck passing through a ring on the stake and they were simultaneously strangled and burnt. In later years in England, some burnings only took place after the convict had already hanged for a half-hour. In some Nordic and German burnings, convicts had containers of gunpowder tied to them or were tied to ladders and then swung into fully burning bonfires. A container of gunpowder tied at the neck might be used to bring about a quicker (and thus more merciful) death, since the victim would suffer only until the gunpowder was heated enough to explode. Some victims refused this, however.

Historical usage

Burning was used as a means of execution in many ancient societies. According to ancient reports, Roman authorities executed many of the early Christian martyrs by burning. These reports claim that in some cases they failed to be burnt, and had to be beheaded instead. However, all such ancient manuscripts were copied by Christian monks, and even Catholic sources state that many of these claims were invented. Under the Byzantine Empire, burning was introduced as a punishment for recalcitrant Zoroastrians, due to the belief that they worshipped fire.

In 1184, the Synod of Verona legislated that burning was to be the official punishment for heresy. This decree was later reaffirmed by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215, the Synod of Toulouse in 1229, and numerous spiritual and secular leaders up through the 17th century.

Among the best known convicts to be executed by burning were Jacques de Molay (1314), Jan Hus (1415), St Joan of Arc (May 30, 1431), Giordano Bruno (1600), and Avvakum (1682).

In the United Kingdom the traditional punishment for women found guilty of treason was to be burnt at the stake, while men were hanged, drawn and quartered. There were two types of treason, high treason for crimes against the Sovereign and petty treason for the murder of one's lawful superior, including that of a husband by his wife. In 1790 Sir Benjamin Hammett introduced a bill into parliament to end what is now widely considered a barbaric practice. He explained that the year before as Sheriff of London he had been responsible for the burning of Catherine Murphy, found guilty of counterfeiting, but that he had allowed her to be hanged first. He pointed out that as the law stood, he himself could have been found guilty of a crime in not carrying out the lawful punishment and, as no woman had been burnt alive in the UK for over fifty years, so could all those still alive who had held an official position at all of the previous burnings. The act was passed by parliament and given royal assent by George III (30 George III. C. 48).[1]

The use of fire in capital punishment is prohibited under Islamic Law.