Capital punishment in the United States

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

| Executions since 1976, by jurisdiction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Executions since 1976 (as of November 4, 2005)[1] |

Inmates on Death Row (as of July 1, 2005)[2] |

| Texas | 352 | 414 |

| Virginia | 94 | 23 |

| Oklahoma | 79 | 97 |

| Missouri | 66 | 55 |

| Florida | 60 | 388 |

| Georgia | 39 | 112 |

| North Carolina | 36 | 192 |

| Alabama | 34 | 191 |

| South Carolina | 34 | 77 |

| Louisiana | 27 | 89 |

| Arkansas | 26 | 38 |

| Arizona | 22 | 128 |

| Ohio | 18 | 196 |

| Indiana | 16 | 30 |

| Delaware | 14 | 19 |

| Illinois | 12 | 10 |

| Nevada | 11 | 85 |

| California | 11 | 648 |

| Mississippi | 6 | 70 |

| Utah | 6 | 10 |

| Maryland | 4 | 9 |

| Washington | 4 | 10 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 233 |

| U.S. Federal Gov't. | 3 | 36 |

| Nebraska | 3 | 10 |

| Kentucky | 2 | 37 |

| Montana | 2 | 4 |

| Oregon | 2 | 32 |

| Tennessee | 1 | 108 |

| Idaho | 1 | 21 |

| Connecticut | 1 | 8 |

| Colorado | 1 | 3 |

| New Mexico | 1 | 2 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 0 | 14 |

| Kansas (On December 17, 2004, the death penalty statute of Kansas was declared unconstitutional) |

0 | 7 |

| U.S. Military | 0 | 8 |

| New York (On June 24, 2004, the death penalty statute of New York was declared unconstitutional) |

0 | 2 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 4 |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 0 |

| United States total |

992 | 3,415* |

| no current death penalty statute: Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

* 7 inmates are on death row in more than one state, making total higher than sum of state numbers. |

||

Capital punishment in the United States is officially sanctioned by 38 of the 50 states, as well as by the federal government. The overwhelming majority of executions are performed by the states; the federal government maintains the right to use capital punishment (also known as the death penalty) but does so infrequently. Each state practicing capital punishment has different laws regarding its methods, age limits, and crimes which qualify. The United States is second only to the People's Republic of China in the number of death sentences passed.

Capital punishment is a highly charged issue with many groups and prominent individuals participating in the debate. Arguments for and against it are based on practical, moral and emotional grounds. Advocates for the death penalty support it by claiming to improve the community by making sure that convicted criminals do not find their way out onto the streets to offend again. Opponents of the death penalty claim that "capital punishment cheapens human life and puts government on the same low moral level as criminals who have taken life" (from American Justice Volume 1).

The debate about whether or not the United States should continue to issue the death penalty has been under debate for a long period of time. The death penalty has repeatedly been challenged as being a cruel and unusual punishment and thus unconstitutional under the eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. "The United States is one of the few democracies in the world that maintains the death penalty for particularly serious crimes; whether it should maintain it has been a matter of practical, moral, and constitutional debate" (from American Justice Volume 1).

Between 1973 and 2002, 7,254 death sentences were issued. These had led to 820 executions, 3,557 prisoners on death row—all for murder, 268 who died while incarcerated of natural causes, suicide or murder, 176 whose sentences were commuted by governors or state pardon boards, and 2,403 who were released, retried or resentenced by the courts.[3] There were 59 executions in 2004.

Most notably, 67% of capital convictions are eventually overturned, mainly on procedural grounds although some were exonerated.[4][5] Seven percent of those whose sentences were overturned between 1973 and 1995 have been found innocent. Ten percent were retried and resentenced to death.[6]

Contents |

History

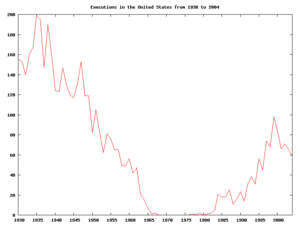

The most comprehensive source (the Espy file) lists fewer than 15,000 people executed in United States and its predecessors between 1608 and 1991.[7] The People's Republic of China executed more than this number just in the 1990s. 4,661 executions occurred in the U.S. in the period 1930 to 2002 with about two-third of the executions occurring in the first 20 years.[8] Additionally the United States Army executed 160 soldiers between 1930 and 1961. The last United States Navy execution was in 1849.

Capital punishment was suspended in the United States between 1967 and 1976 as a result of several decisions of the United States Supreme Court, primarily the case of Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)*. In this case, the court found the application of the death penalty to be unconstitutional, on the grounds of cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the eighth amendment to the United States Constitution.

In Furman, the United States Supreme Court specifically struck down Georgia's "unitary trial" procedure, in which the jury was asked to return a verdict of guilt or innocence and, simultaneously, determine whether the defendant would be punished by death or life imprisonment. Their line of reasoning was further clarified in the Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976)* and Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976), 431 U.S. 633 (1977)*, which explicity forbade any state from punishing a specific form of murder (such as that of a police officer) with a mandatory death penalty. The 1977 Coker v. Georgia ruling barred the death penalty for rape of a 16 year old married female, and, by implication, for any offense other than murder.

In 1976, contemporaneously with Woodson and Roberts, the Court decided Gregg v. Georgia, and upheld a procedure in which the trial of capital crimes was bifurcated into guilt-innocence and sentencing phases. Executions resumed on January 17, 1977 when Gary Gilmore went before a firing squad in Utah. Since 1976, 946 people have been executed, almost exclusively by the states. Texas has accounted for over a third of modern executions (337 as of January 2005); the federal government has executed only 3 people in the last 27 years. California has the greatest number of prisoners on death row, but has held relatively few executions.

Crimes subject to death penalty

Crimes subject to the death penalty vary by jurisdiction. All jurisdictions which use capital punishment have murder as a crime which is subject to the death penalty, although many jurisdictions require additional aggravating circumstances. Treason is a capital offense in several jurisdictions. Other capital crimes include: aggravated kidnapping in Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and South Carolina; train wrecking and perjury which leads to someone being executed in California; aircraft hijacking in Georgia and Mississippi; aggravated rape of victim under age 12 in Louisiana; capital sexual battery in Florida; and capital narcotics conspiracy in Florida and New Jersey. Federal death penalty crimes are various degrees and types of murder as well as treason, espionage, large scale drug trafficking, and attempting to kill any officer, juror, or witness in cases involving a Continuing Criminal Enterprise. There are 14 crimes subject to the death penalty under U.S. military law; some of them, such as desertion, are only applicable in times of war.

Unless the person is being tried in a bench trial (they chose to be tried only by a judge) the sentence must be handed down by a jury, not by a judge alone. The jury must hand down the sentence at the conclusion of a separate penalty phase of the trial (at least implying the jurors who sentence the person to death were the same jurors who convicted him or her of the crime). Ring v. Arizona 536 U.S. 584 (2002).

In practice, no one has been executed for a crime other than murder or conspiracy to murder since 1964, when James Coburn was executed for robbery in Alabama on 4 September. All death row inmates in 2002 were convicted of murder. The last time someone executed solely for other crimes were:

- Rape - Ronald Wolfe on 8 May 1964 in Montana.

- Criminal assault - Rudolph Wright on 11 January 1962 in California

- Kidnapping - Billy Monk on 21 November 1960 in California

- Espionage - Ethel and Julius Rosenberg on 19 June 1953 in New York (Federal execution)

- Burglary - Frank Bass on August 8, 1941 in Alabama

- Arson - George Hughes, George Smith, Asbury Hughes on August 1, 1884 in Alabama

- "Guerrilla Activity" - Champ Ferguson on 21 October 1865 in Tennessee

- Piracy - Nathaniel Gordon on 21 February 1862 in New York (Federal execution)

- Treason - John Conn in 1862 in Texas

- Slave revolt - Slaves named Caesar, Sam and Sanford on 19 October 1860 in Alabama

- Aiding a runaway slave - Starling Carlton in 1859 in South Carolina

- Theft - Slave named Jake on 3 December 1855 in Alabama

- Horse stealing - James Wilson and Fred Salkman on 28 November 1851 in California

- Forgery - 6 March 1840 in South Carolina

- Counterfeiting - Thomas Davis on 11 October 1822 in Alabama

- Sodomy/buggery/bestiality - Joseph Ross December 20, 1785 in Pennsylvania

- Concealing the birth/death of an infant - Hannah Piggen in 1785 in Massachusetts

- Witchcraft - Black person named Manuel on 15 June 1779 in (present-day) Illinois

Methods

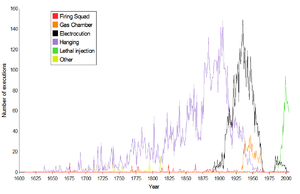

Various methods have been used in the history of the American colonies and the United States but only five methods are currently used. Historically, burning, pressing, gibbeting or hanging in chains, breaking on wheel and bludgeoning were used for a small number of executions while hanging was the most common method. The last person burned to death was a black slave in South Carolina in August 1825. The last person to be hung in chains was a murderer named John Marshall in West Virginia on April 4, 1913.

Currently lethal injection is the method used or allowed in 37 of the 38 states which allow the death penalty and by the federal government. Nebraska requires electrocution. Other states also allow electrocution, gas chambers, hanging and the firing squad. From 1976 to 2004, out of 944 executions: 776 have been by lethal injection, 153 by electrocution, 11 by gas chamber, 3 by hanging, and 2 by firing squad.

The use of lethal injection has become standard. From 2001, only 3 out of 273 executions have been by a different method. The last execution by any other method was the use of the electric chair on May 28, 2004 when James Neil Tucker was executed in South Carolina. The last use of the gas chamber occurred on 24 February 1999 when Karl LaGrand was executed in Arizona, the last use of hanging was on 25 January 1996 when Delaware hanged Billy Bailey and the firing squad was also last used in 1996 when John Albert Taylor was shot in Utah on 26 January.

The electric chair was the major method of execution during most of the 20th century. They developed a special nickname: Old Sparky. Some, particularly that of Florida, were noted for malfunctions, which caused discussion of their cruelty and resulted in a shift to lethal injection as the major method of execution. Regardless of the method, an hour or two before the execution, the condemned person has a last meal and religious services.

Executions are carried out in private with only invited persons able to view the proceedings. The last public execution was the hanging of Rainey Bethea on 14 August 1936 in Owensboro, Kentucky.

Ages of condemned prisoners

The minimum age at time of crime to be subject to the death penalty is 18. Until March 2005, the United States was one of only eight countries in the world to practice the death penalty on juveniles—criminals aged under 18 at the time of their crime. The remaining nations are Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Since 1642 (in the 13 colonies, the United States under the Articles of Confederation, and the current United States) an estimated 364 juvenile offenders have been put to death by states and the federal government. Twenty-two of the executions occurred after 1976, in seven states. Due to the slow process of appeals, it was highly unusual for a condemned person to be under 18 at the time of execution. The last execution of a juvenile may have been Leonard Shockey, executed on April 10, 1959 at the age of 17. No one has been under age 19 at time of execution since at least 1964. [9][10]

Before 2005, of the 38 U.S. states that allow capital punishment:

- 19 states and the federal government had set a minimum age of 18,

- Five states had set a minimum age of 17, and

- 14 states had explicitly set a minimum age of 16, or were subject to the Supreme Court's imposition of that minimum.

Sixteen was held to be the minimum permissible age in the 1988 Supreme Court of the United States decision of Thompson v. Oklahoma. The Supreme Court, considering the case Roper v. Simmons, in March 2005, found execution of juvenile offenders unconstitutional by a 5-4 margin. State laws have not been updated to conform with this decision. Under the US system, unconstitutional laws do not need to be repealed, but are instead held to be unenforceable.

Distribution of sentences

Within the context of the overall murder rate, the death penalty cannot be said to be widely or routinely used in the United States; in recent years the average has been about one execution for about every 700 murders committed, or 1 execution for about every 325 murder convictions.

It is noted that the death penalty is sought and applied more often in some jurisdictions, not only between states but within states. A 2004 Cornell University study showed that while 2.5% of murderers convicted nationwide were sentenced to the death penalty, in Nevada 6% were given the death penalty. Texas gave only 2% of murderers the death sentence, less than the national average. Texas, however, executed 40% of those sentenced, which was about 4 times higher than the national average. California had executed only 1% of those sentenced.

Only 1.4 % of those executed since 1976 have been women.

African Americans make up 42% of death row inmates while making up only 12% of the general population. (They have made up 34% of those actually executed since 1976.)[11] Conversely, others note that this is lower than the 50% of the total prison population which is African American and that whites are in fact twice as likely as African Americans to receive the death penalty, and are also executed more quickly after sentencing.[12] Academic studies indicate that the single greatest predictor of whether a death sentence is given, however, is not the race of the defendant, but the race of the victim. Because most violence is intraracial, this accounts for the statistics with respect to whites on death row. According to a 2003 Amnesty International report, blacks and whites were the victims of murder in almost equal numbers, yet 80 % of the people executed since 1977 were convicted of murders involving white victims.[13]

Suicide on death row

The suicide rate of death row inmates was found by Lester Tartaro to be 113 per 100,000 for the period 1976–1999. This is about ten times the rate of suicide in the United States as a whole and about six times the rate of suicide in the general U.S. prison population.

Controversy over use of death penalty

Various groups oppose or support the use of capital punishment. Amnesty International and many bishops of the Roman Catholic Church oppose capital punishment on moral grounds, while the Innocence Project works to free wrongly convicted prisoners, including death row inmates, based on newly available DNA tests. Other groups, such as the Southern Baptists, law enforcement, and some victims rights groups support capital punishment. Death penalty supporters argue that opinion polls consistently show a majority of the public support the death penalty, with a May 2005 Gallup poll had 74% of respondees in "favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder".[14] Opponents of the death penalty argue that the poll results depend on the wording of the question, and that when life imprisonment without parole and making restitution to the victim are offered as an alternative, a majority of the American public oppose the death penalty.[15]

Religious groups are widely split on the issue of capital punishment,[16] generally with more conservative groups more likely to support it and more liberal groups more likely to oppose it.

Debate over the death penalty centers around four issues: whether it is morally correct to kill; whether the death penalty serves as a deterrent; whether the penalty is being applied fairly across racial, social, and economic classes; and whether the irrevocability of the penalty is justified considering possible new evidence or future revelations of improper conduct by the state. It is also claimed that the financial costs of a complete death penalty case exceed the total costs of a lifetime of incarceration. Between 1976 and 2003, less than 2% of death row prisoners were exonerated, while others had their sentences reduced for other reasons. This amounted to 112 prisoners released.

Since the death penalty was reinstated in Illinois in 1977, 12 men have been executed. During that same period, 13 innocent men were freed from death row.[17] This finding prompted the outgoing governor of Illinois, George H. Ryan, to commute all death penalties in his state in January 2003. It should be noted that at the time, he was under investigation, and as of October 2005, is currently being tried in Chicago on charges of fraud.[18] When they elected Rod Blagojevich, a Democrat, as the new governor in 2002, one of his first acts (through the new Illinois Attorney General, Lisa Madigan[19]) was to unsuccessfully try and revoke some of Ryan's commutations.[20]

See also

- List of individuals executed by the United States

- Lists of individuals executed in Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming.

External links

Anti-death penalty

- National Coalition To Abolish The Death Penalty

- Death Penalty Information Center

- The Innocence Project

- Truth In Justice

- Attrition of capital cases

- Amnesty International USA campaign to abolish the death penalty

- Campaign to end the Death Penalty

- Religious Organizing - Against the Death Penalty

- Human Writes

- Death Penalty Focus

Pro-death penalty

- Pro Death Penalty.com

- Pro Death Penalty Resource Page

- Clark County, IN Prosecutor's Page on capital punishment.

More information

- Last Meals on Death Row

- Execution of Caleb Adams - Story of Caleb Adams, who was publicly executed in Windham, Connecticut on November 29, 1803 for the murder of 6-year-old Oliver Woodworth.

References

- Banner, Stuart (2002). The Death Penalty: An American History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674007514.

- Dow, David R., Dow, Mark (eds.) (2002). Machinery of Death. The Reality of America's Death Penalty Regime. Routledge, New York. ISBN 0415932661 (cloth), ISBN 041593267X (paperback)

(this book provides critical perspectives on the death penalty; it contains a foreword by Christopher Hitchens)