Special relativity

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

A simple introduction to this subject is provided in Special relativity for beginners

Special relativity (SR) or the special theory of relativity is the physical theory published in 1905 by Albert Einstein. It replaced Newtonian notions of space and time and incorporated electromagnetism as represented by Maxwell's equations. The theory is called "special" because it applies the principle of relativity only to the "restricted" or "special" case of inertial reference frames in flat spacetime, where the effects of gravity can be ignored. Ten years later, Einstein published his general theory of relativity (general relativity, "GR") which incorporated these effects.

For History and motivation, see the article: History of special relativity

Contents |

Postulates

Main article: Postulates of special relativity

1. First postulate (principle of relativity)

- The laws of electrodynamics and optics will be valid for all frames of reference in which the laws of mechanics hold good (non-accelerating frames).

In other words: Every physical theory should look the same mathematically to every inertial observer; the laws of physics are independent of the state of inertial motion.

2. Second postulate (invariance of c)

- Light is always propagated in empty space with a definite velocity c that is independent of the state of motion of the emitting body; here the velocity of light c is defined as the two-way velocity, determined with a single clock.

In other words: The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted c, is the same to all inertial observers, and does not depend on the velocity of the object emitting the light.

Status

Main article: Status of special relativity

Special relativity is only accurate when gravitational effects are negligible or very weak, otherwise it must be replaced by general relativity. At very small scales, such as at the Planck length and below, it is also possible that special relativity breaks down, due to the effects of quantum gravity. However, at macroscopic scales and in the absence of strong gravitational fields, special relativity is now universally accepted by the physics community and experimental results which appear to contradict it are widely believed to be due to unreproducible experimental error.

Because of the freedom one has to select how one defines units of length and time in physics, it is possible to make one of the two postulates of relativity a tautological consequence of the definitions, but one cannot do this for both postulates simultaneously, as when combined they have consequences which are independent of one's choice of definition of length and time.

Special relativity is mathematically self-consistent, and is also compatible with all modern physical theories, most notably quantum field theory, string theory, and general relativity (in the limiting case of negligible gravitational fields). However special relativity is incompatible with several earlier theories, most notably Newtonian mechanics. See Status of special relativity for a more detailed discussion.

A few key experiments can be mentioned that led to special relativity:

- The Trouton-Noble experiment showed that the torque on a capacitor is independent on position and inertial reference frame - such experiments led to the first postulate

- The famous Michelson-Morley experiment demonstrated the directional invariance of the two-way speed of light - "the speed of light" as defined in the second postulate.

A number of experiments have been conducted to test special relativity against rival theories. These include:

- Kaufman's experiment- electron deflection in exact accordance with Lorentz-Einstein prediction

- Hamar experiment - no "ether flow obstruction"

- Kennedy-Thorndike experiment - time dilation in accordance with Lorentz transformations

- Rossi-Hall experiment - relativistic effects on a fast-moving particle's half-life

- Experiments to test emitter theory demonstrated that the speed of light is independent of the speed of the emitter.

In addition, particle accelerators run almost every day somewhere in the world, and routinely accelerate and measure the properties of particles moving at near lightspeed. Many effects seen in particle accelerators are highly consistent with relativity theory and are deeply inconsistent with the earlier Newtonian mechanics.

Consequences

Main article: Consequences of Special Relativity

Special relativity leads to different physical predictions than Galilean relativity when relative velocities become comparable to the speed of light. The speed of light is so much larger than anything humans encounter that some of the effects predicted by relativity are initially counter intuitive.

- The time lapse between two events is not invariant from one observer to another, but is dependent on the relative speeds of the observers' reference frames. (See Lorentz transformation equations)

- Two events that occur simultaneously in different places in one frame of reference may occur at different times in another frame of reference (lack of absolute simultaneity).

- The dimensions (e.g. length) of an object as measured by one observer may differ from the results of measurements of the same object made by another observer. (See Lorentz transformation equations)

- The twin paradox concerns a twin who flies off in a spaceship travelling near the speed of light. When he returns he discovers that his twin has aged much more rapidly than he has (or he aged more slowly).

- The ladder paradox involves a long ladder travelling near the speed of light and being contained within a smaller garage.

Lack of an absolute reference frame

Special Relativity rejects the idea of any observable absolute ('unique' or 'special') frame of reference; rather physics must look the same to all observers travelling at a constant velocity (inertial frame). This 'principle of relativity' dates back to Galileo, and is incorporated into Newtonian Physics. In the late 19th Century, some physicists suggested that the universe was filled with a substance known as "aether" which transmitted Electromagnetic waves. Aether constituted an absolute reference frame against which speeds could be measured. Aether had some wonderful properties: it was sufficiently elastic that it could support electromagnetic waves, those waves could interact with matter, yet it offered no resistance to bodies passing through it. The results of various experiments, including the Michelson-Morley experiment, suggested to some that the Earth was always 'stationary' relative to the Aether - something that is difficult to explain. The most elegant solution was to discard the notion of Aether and an absolute frame, and to adopt Einstein's postulates.

Space, time, and velocity

In this animation, the dashed line is the world line of a particle whose view of spacetime is being illustrated. The balls are placed at regular intervals of proper time along the world line. The solid diagonal lines are the light cones for the observer's current event, and intersect at that event. The small dots are other arbitrary events in the spacetime. For the observer's current instantaneous inertial frame of reference, the vertical direction is temporal and the horizontal direction is spatial.

The slope of the world line (deviation from being vertical) is the velocity of the particle on that section of the world line. So at a bend in the world line the particle is being accelerated. Note how the view of spacetime changes as current event passes through the accelerations, changing the instantaneous inertial frame of reference. These changes are governed by the Lorentz transformations. Also note that:

• the balls on the world line before/after future/past accelerations are more spaced out due to time dilation.

• events which were simultaneous before an acceleration are at different times afterwards (due to the relativity of simulataneity),

• events pass through the light cone lines due to the progression of proper time, but not due to the change of views caused by the accelerations,and

• the world line always remains within the future and past light cones of the current event.

Main article: Lorentz transformation

An event is an occurrence that can be assigned a single unique time and location in space: It is a "point" in space-time. For example, the explosion of a firecracker is an "event" to a good approximation. We can completely specify an event by its four space-time coordinates: The time of occurrence, and its 3-dimensional spatial location. Suppose we have two systems S and S', whose spatial axes are co-aligned and are moving at a constant velocity (v) with respect to each other along their x axes. If an event has space-time coordinates (t,x,y,z) in system S and (t',x',y',z') in S', and their origins coincide (in other words (0,0,0,0) in S coincides with (0,0,0,0) in S'), then the Lorentz transformation specifies that these coordinates are related in the following way:

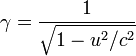

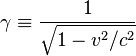

where  is called the Lorentz factor and c is the speed of light in a vacuum.

is called the Lorentz factor and c is the speed of light in a vacuum.

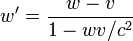

If the observer in S sees an object moving along the x axis at velocity w then the observer in the S' system will see the object moving with velocity w' where

.

.

This equation can be derived from the space and time transformations above. Notice that if the object is moving at the speed of light in the S system (i.e. w = c), then it will also be moving at the speed of light in the S' system. Also, if both w and v are small with respect to the speed of light, we will recover the intuitive Galilean transformation of velocities: w' = w − v.

Mass, momentum, and energy

In addition to modifying notions of space and time, special relativity forces one to reconsider the concepts of mass, momentum, and energy, all of which are important constructs in Newtonian mechanics. Special relativity shows, in fact, that these concepts are all different aspects of the same physical quantity in much the same way that it shows space and time to be interrelated.

There are a couple of (equivalent) ways to define momentum and energy in SR. One method uses conservation laws. If these laws are to remain valid in SR they must be true in every possible reference frame. However, if one does some simple thought experiments using the Newtonian definitions of momentum and energy one sees that these quantities are not conserved in SR. One can rescue the idea of conservation by making some small modifications to the definitions to account for relativistic velocities. It is these new definitions which are taken as the correct ones for momentum and energy in SR.

Given an object of invariant mass m_0 traveling at velocity u the energy and momentum are given by

where γ (the Lorentz factor) is given by

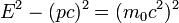

and c is the speed of light. The term γ occurs frequently in relativity, and comes from the Lorentz transformation equations. The energy and momentum can be related through the formula

which is referred to as the relativistic energy-momentum equation. These equations can be more succinctly stated using the four-momentum Pa and the four-velocity Ua as

- Pa = m0Ua

which can be viewed as a relativistic analogue of Newton's second law.

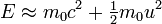

For velocities much smaller than those of light γ can be approximated using a Taylor series expansion and one finds that

Barring the first term in the energy expression (discussed below), these formulas agree exactly with the standard definitions of Newtonian kinetic energy and momentum. This is as it should be, for special relativity must agree with Newtonian mechanics at low velocities.

Looking at the above formulas for energy, one sees that when an object is at rest (u = 0 and γ = 1) there is a non-zero energy remaining:

This energy is referred to as rest energy. The rest energy does not cause any conflict with the Newtonian theory because it is a constant and, as far as kinetic energy is concerned, it is only differences in energy which are meaningful.

Taking this formula at face value, we see that in relativity, mass is simply another form of energy. This formula becomes important when one measures the masses of different atomic nuclei. By looking at the difference in masses, one can predict which nuclei have extra stored energy which can be released by nuclear reactions, providing important information which was useful in the development of the nuclear bomb. The implications of this formula on 20th century life have made it one of the most famous equations in all of science.

On mass

Introductory physics courses and some older textbooks on special relativity sometimes define a relativistic mass which increases as the velocity of a body increases. According to the geometric interpretation of special relativity, this is often depreciated and the term 'mass' is reserved to mean 'rest mass' and is thus independent of the inertial frame, i.e., invariant.

Using the relativistic mass definition, the mass of an object may vary depending on the observer's inertial frame in the same way that other properties such as its length may do so. Defining such a quantity may sometimes be useful in that doing so simplifies a calculation by restricting it to a specific frame. For example, consider a body with an invariant mass m0 moving at some velocity relative to an observer's reference system. That observer defines the relativistic mass of that body as:

"Relativistic mass" should not be confused with the "longitudinal" and "transverse mass" definitions that were used around 1900 and that were based on an inconsistent application of the laws of Newton: those used F=ma for a variable mass, while relativistic mass corresponds to Newton's dynamic mass in which p=mv and F=dp/dt.

Note also that the body does not actually become more massive in its proper frame, since the relativistic mass is only different for an observer in a different frame. The only mass that is frame independent is the invariant mass. When using the relativistic mass, the used reference frame should be specified if it isn't already obvious or implied.

Physics textbooks sometimes use the relativistic mass as it allows the students to utilize their knowledge of Newtonian physics to gain some intuitive grasp of relativity in their frame of choice (usually their own!). "Relativistic mass" is also consistent with the concepts "time dilation" and "length contraction". It goes almost without saying that the increase in relativistic mass does not come from an increased number of atoms in the object. Instead, each atom, indeed each subatomic particle increases its relativistic mass as the object accelerates.

Simultaneity and causality

Special relativity holds that events that are simultaneous in one frame of reference need not be simultaneous in another frame of reference.

The interval AB in the diagram to the right is 'time-like'; i.e., there is a frame of reference in which event A and event B occur at the same location in space, separated only by occurring at different times. If A precedes B in that frame, then A precedes B in all frames. It is hypothetically possible for matter (or information) to travel from A to B, so there can be a causal relationship (with A the cause and B the effect).

The interval AC in the diagram is 'space-like'; i.e., there is a frame of reference in which event A and event C occur simultaneously, separated only in space. However there are also frames in which A precedes C (as shown) and frames in which C precedes A. Barring some way of traveling faster than light, it is not possible for any matter (or information) to travel from A to C or from C to A. Thus there is no causal connection between A and C.

The geometry of space-time

SR uses a 'flat' 4-dimensional Minkowski space, which is an example of a space-time. This space, however, is very similar to the standard 3 dimensional Euclidean space, and fortunately by that fact, very easy to work with.

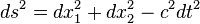

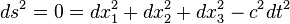

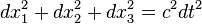

The differential of distance(ds) in cartesian 3D space is defined as:

where (dx1,dx2,dx3) are the differentials of the three spatial dimensions. In the geometry of special relativity, a fourth dimension, time, is added, with units of c, so that the equation for the differential of distance becomes:

In many situations it may be convenient to treat time as imaginary (e.g. it may simplify equations), in which case t in the above equation is replaced by i.t', and the metric becomes

If we reduce the spatial dimensions to 2, so that we can represent the physics in a 3-D space

We see that the null geodesics lie along a dual-cone:

defined by the equation

or

Which is the equation of a circle with r=c*dt. If we extend this to three spatial dimensions, the null geodesics are continuous concentric spheres, with radius = distance = c*(+ or -)time.

This null dual-cone represents the "line of sight" of a point in space. That is, when we look at the stars and say "The light from that star which I am receiving is X years old.", we are looking down this line of sight: a null geodesic. We are looking at an event  meters away and d/c seconds in the past. For this reason the null dual cone is also known as the 'light cone'. (The point in the lower left of the picture below represents the star, the origin represents the observer, and the line represents the null geodesic "line of sight".)

meters away and d/c seconds in the past. For this reason the null dual cone is also known as the 'light cone'. (The point in the lower left of the picture below represents the star, the origin represents the observer, and the line represents the null geodesic "line of sight".)

The cone in the -t region is the information that the point is 'receiving', while the cone in the +t section is the information that the point is 'sending'.

The geometry of Minkowski space can be depicted using Minkowski diagrams, which are also useful in understanding many of the thought-experiments in special relativity.

Relativity and unifying Electromagnetism

Using the relativistic transformations it can be shown that the magnetic field generated by a current in a wire disappears and becomes a purely electrostatic field in a particular comoving frame of reference.

This is due to the lack of simultaneity of the charges entering and leaving a wire and the Lorentz contraction of the wire and the moving charges. The wire and current ends up with a net charge and no magnetic field. The converse is also obviously true; so an electrostatic effect may appear to be caused by magnetism to a different observer.

It can therefore be seen that electrostatics and magnetism are simply two sides of the same coin, hence the term Electromagnetism. It turns out that they can be mathematically described by a four-vector.

Related topics

- People: Arthur Eddington | Albert Einstein | Hendrik Lorentz | Hermann Minkowski | Bernhard Riemann | Henri Poincaré | Alexander MacFarlane | Harry Bateman | Robert S. Shankland

- Relativity: Theory of relativity | principle of relativity | general relativity | frame of reference | inertial frame of reference | Lorentz transformations

- Physics: Newtonian Mechanics | spacetime | speed of light | simultaneity | cosmology | Doppler effect | relativistic Euler equations | Aether drag hypothesis

- Math: Minkowski space | four-vector | world line | light cone | Lorentz group | Poincaré group | geometry | tensors | split-complex number

- Philosophy: actualism | convensionalism | formalism

External links

- Beneath the Foundations of Spacetime Special relativity can be derived with moving rulers in such a way that the astonishing connection between space and time can be clearly understood.

- Relativity calculator Geometric calculations of relativistic problems such as the addition of velocities. Note that it is Java-based and can take several minutes to load using a 56k modem.

- Relativity in its Historical Context The discovery of special relativity was inevitable, given the momentous discoveries that preceded it.

- Nothing but Relativity There are many ways to derive the Lorentz transformation without invoking Einstein's constancy of light postulate. The path preferred in this paper restates a simple, established approach.

- Reflections on Relativity A complete online book on relativity with an extensive bibliography.

- Special Relativity Lecture Notes is a standard introduction to special relativity containing illustrative explanations based on drawings and spacetime diagrams from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Brane World Mach Principles and the Michelson-Morley experiment

- Petites expériences de pensée : five interesting thought experiments about special relativity quoted in the French Language Wikipedia.

- Special relativity theory made intuitive : a new approach to explain the theoretical meaning of Special Relativity from an intuitive geometrical viewpoint

- Special Relativity Stanford University, Helen Quinn, 2003

- Free eBook of Relativity: the Special and General Theory at Project Gutenberg, by Albert Einstein

- Special Relativity This is chapter two of Christoph Schiller's 1000 page walk through the whole of physics, from classical mechanics to relativity, electrodynamics, thermodynamics, quantum theory, nuclear physics and unification. 61 pages.

- "Why Einstein may have got it wrong" by David Adam, The Guardian, April 11, 2005.

- Through Einstein's Eyes The Australian National University. Relativistic visual effects explained with movies and images.

- Greg Egan's Foundations.

- Short Essay Explaining Special Relativity by S. Abbas Raza of 3 Quarks Daily

- Einstein Light tutorial

- Enlightening Ideas a humoristic animation about the special relativity for the general public, Yannick Mahé, 2005

References

Textbooks

- Einstein, Albert. "Relativity- The Special and the General Theory", Routledge Classics 1993 ISBN 0-415-25538-4

- Tipler, Paul; Llewellyn, Ralph (2002). Modern Physics (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0716743450

- Schutz, Bernard F. A First Course in General Relativity, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521277035

- Taylor, Edwin, and Wheeler, John (1992). Spacetime physics (2nd ed.). W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0716723271

- Einstein, Albert (1996). The Meaning of Relativity. Fine Communications. ISBN 1567311369

- Geroch, Robert (1981). General Relativity From A to B. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226288641

Journal articles

- On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, A. Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 17:891, June 30, 1905 (in English translation)

- Wolf, Peter and Gerard, Petit. "Satellite test of Special Relativity using the Global Positioning System," Physics Review A 56 (6), 4405-4409 (1997).

- Will, Clifford M. "Clock synchronization and isotropy of the one-way speed of light," Physics Review D 45, 403-411 (1992).

- Alvager et al., "Test of the Second Postulate of Special Relativity in the GeV region," Physics Letters 12, 260 (1964).

| General subfields within physics | |

|

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics | Classical mechanics | Condensed matter physics | Continuum mechanics | Electromagnetism | General relativity | Particle physics | Quantum field theory | Quantum mechanics | Special relativity | Statistical mechanics | Thermodynamics |

|